Taste the Misery

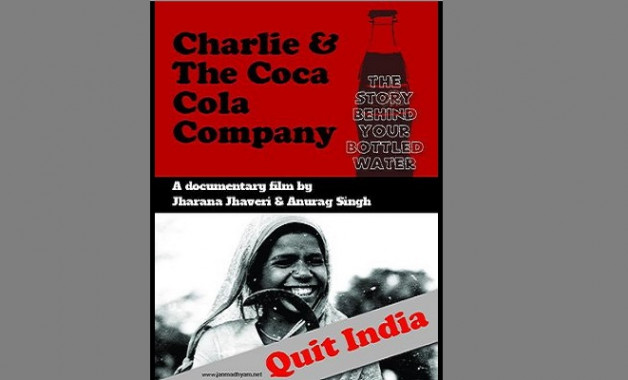

After a year-long battle to secure a certificate for her documentary film ‘Charlie and the Coca Cola Company’, film-maker Jharna Jhaveri has filed an application before the Delhi Court to allow her to screen it for the court and seek an early hearing of her case challenging the ban on her film for its ‘political motives’.

In 2004, farmers of Mehdiganj and Balia in Uttar Pradesh, began a struggle against the harmful effects of the extraction of groundwater for the Coca Cola plant at almost negligible cost. Jhaveri and film maker Anurag Singh began documenting the struggle from 2007 and looked at the manner in which policies are framed to set up such plants in backward regions, the effects of such water extraction on the water table, and the loss of land and livelihood of farmers as a result.

In August last year, ‘Charlie and the Coca Cola Company’ was denied a certificate from the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) on the grounds that “the film more than education, is misleading and political motive.” Aggrieved, the film-makers filed an appeal with the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT), New Delhi which went one step further in rejecting it. On March 8, 2017, the FCAT order said that the film contained a large number of ‘defamatory imputations’ and that the ‘documentary has been made with a sole objective of shutting down the Coca Cola plant’.

It also maintained that the film was made with ‘fictional actors’, completely negating the voices of the affected villagers who lived in the vicinity of the bottling plant.

Jhaveri’s petition challenging the ban came up in July before Justice Sanjeev Sachdeva but even before it could be heard, the court had risen for the day. The next hearing of the case was posted for February 12, 2018. In the interim, the film cannot be screened publicly.

If the denial of a certificate for screening has sounded the death-knell for many documentaries, the delays in court hearings of cases challenging these denials have become the last nail in the coffin. Senior Supreme Court advocate KTS Tulsi, who is representing Jhaveri, told The Hoot that she had a good case and he was hopeful of an early hearing.

In her petition, Jhaveri said that there was no question of any defamatory imputations made in the film. The petition said: ‘The documentary from beginning to the end has simply shown the nationwide protests by farmers against aerated drinks companies including the Coca Cola company with respect to severe abuse of water and interviews taken in this regard, of the local villagers, farmers and those employed with the Coca Cola company. There is not even a single scene in the said film which can be attributed to the same being politically motivated’.

Challenging the FCAT contention that the film was defamatory to a particular company, the petition draws upon the Delhi High Court order in Prakash Jha Productions v. Bata India Ltd. &Ors. MANU/DE/5509/2012 that the theme of social relevance must be upheld to protect freedom of expression.

The film is around 2.20 hours long. It begins by tracking the struggle of the farmers to ensure the supply of clean water for their land and for their own use. The plant, set up by Coca Cola, had steadily led to the acute depletion of groundwater thereby turning lands in the vicinity completely barren with no water for farmers to till their fields, forcing many to sell off their land, the petition said.

Further, the film showcases the plight of workers employed by these companies, who are compelled to work in unsafe conditions without any protection and on abysmally low wages.

The film moves to the 2003 protest of farmers of Plachimada, Kerala, and the report of the Central Pollution Control Board which led to the closing down of the plant, it interviews residents of Balia, in Uttar Pradesh and quotes a school teacher who speaks of the explosion inside the Daban Coke plant after which effluents leaked into the river, resulting in the death of fish.

The film ends with the interview of a young American student ‘Charlie’, who comes to Varanasi on an internship, witnesses the havoc caused by water policies that are more favourable to big aerated bottling plants than to farmers and realizes that his education is part-funded by a scholarship from Coca Cola.

Jhaveri told The Hoot that she had begun tracking the issue of water from as far back as 1995, when she, along with Anurag Singh, designed and conducted film-making modules for officers. “We got to know of the way in which policies are framed, who gets left out, who takes the decisions,” she said.

The duo, who founded Janmadhyam Films in 1992, got involved in the organizing of the ‘rally for the valley’ in 1999 and then made a film on the Narmada issue (‘Kaisejeebo re’ or How shall I survive, my friend), on the plight of villagers whose land and houses were submerged by the dam project.

From Narmada to a film on the privatisation of water and the damage done to the environment by the world’s largest soft drinks manufacturing company took more than six years in the making.

Jhaveri says that she needed to be extremely thorough about the research and information the film sought to put out. “Coca Cola is one of the most successful corporations in the world. The worldwide association with it is happiness. So we need to explain what exactly it is doing to the water table, how it operates in backward areas which are water extensive, utilizes seven to ten litres of water for every 300ml of Coke, and the pollution of the groundwater table”, she said.

The struggle to make the film has resulted in near bankruptcy for her, as she sold her house to finance it. “I applied for a certificate this time because I wanted a theatrical release. But the entire process of applying for a certificate and seeking this permission is so dehumanizing,” she says, adding that the issue of water and its privatization is crucial for society.

“I feel people must be able to watch it freely and debate it. Of course, the struggle of the villagers I was documenting is all but over but the larger battle still remains. I feel angry at what we have done to our rivers. If more people see this and understand what we are doing, perhaps we can begin to stop killing our rivers,” she said.

Jhaveri is clear that ‘Charlie and the Coca Cola Company’ is not defamatory and merely looks at water privatisation through the eyes of villagers imperilled by the soft drinks factory on the land they once tilled. Coca Cola has kept silent about the film and it doesn’t even need to do anything at the moment as the CBFC and FCAT are more than ably batting for it.

The question really is whether they should do so, or let a discerning public decide whether the film defames the company or uncovers an ugly truth.