Anonymous sourcing at the New York Times

Figures for 2015

Reprinted from Fair.org

Journalism’s Dark Matter

Reed Richardson

Journalists face numerous ethical and institutional challenges when doing their job. But none of these challenges lays bare the conflicts and compromises involved in reporting the news quite like the use of anonymous sources.

For a profession predicated on demanding transparency and accountability from others, the practice of granting anonymity serves as an inconvenient reminder of journalism’s own messy reality. The implied bargain therein—that the value of the light provided by a source’s information outweighs the cost of casting of a shadow over his or her public identity—trades upon both the judgment and authority of the reporter and his or her news organization.

Journalism, as a profession, has a long, sordid history of misusing and abusing anonymous sources.

In recent years, news organizations have tried to rein in those excesses with more rigorous ethical rules about their use. The Society of Professional Journalists has published recommended best practices, but newspapers and media outlets routinely pick and choose which of these they will follow—if they follow any of them at all—and cobble together their own in-house guidelines. More often than not, however, these anonymity rules work in a prescriptive rather than normative fashion and are reactive in nature, narrowly tailored to correct the latest embarrassing mistake.

One of the New York Times‘ deceptive WMD stories (9/8/02), sourced to “Bush administration officials.”

The New York Times is no exception. In fact, the paper just unveiled yet another update to its rules on granting anonymity earlier this month (3/15/16) after two major anonymous sources stories blew up in the paper’s face last year. This follows more than a decade of false starts and half-measures reaching back to 2004, when the paper finally published an explicit confidential news sources policy after its reputation was publicly battered by the twin scandals of Jayson Blair’s fabulism and its credulous Iraqi WMD coverage. But only a year later, the paper saw the need to further tighten its guidelines, the effect of which “created the potential to profoundly alter the role of confidential sources in the Times‘ newsroom,” according to the (very optimistic) then-Timespublic editor, Byron Calame (11/20/05).

Just two years after that rosy assessment, however, a survey by Columbia University Journalism School students found that the paper had cut down on the use of anonymous sources, but that only one in five instances met the paper’s own citation standards. In 2009, Craig Whitney, the Times standards editor at the time, told Clark Hoyt, Calame’s successor as public editor (3/22/09), an all too familiar tale: “The bar should be far higher than it is before a reporter puts an anonymous quote in and before an editor lets it stay in.” But as FAIR documented (Extra!,11/11), the Times consistently failed to live up to its own standards in the years following that pronouncement as well.

And so, nearly 12 years after the Times‘ first public editor, Daniel Okrent (5/4/04), condemned the “toxic” effect of unnamed sources in the paper, the Times continues to struggle with endemic abuses of anonymity. Current public editor Margaret Sullivan acknowledged as much in a column at the end of 2014 (12/29/14):

One thing is certain: Anonymity continues to be granted to sources far more often than a last-resort basis would suggest…. But 2015 is another year to try to root out what some have called the “anonymice”—and the dubious rationalizations they travel with.

So after all these years of newsroom memos and executive rhetoric, I wondered, what exactly does a year’s worth of anonymous sources now look like at the New York Times? The answer, it turns out, is a journalistic amalgam of frustrating ambiguity and mind-numbing repetition, with moments of stunning negligence and unmitigated triumph mixed in. Far from being a “last resort,” however, anonymous sources remain stubbornly common within the paper, and were, notably, even more likely to be found lurking among high-profile and front-page stories.

If you’re looking for a definitive total of anonymous-source articles published by the Times last year, you won’t find it here. Or anywhere. After sorting and categorizing tens of thousands of data points and poring over hundreds of individual articles, blog posts and columns, I can only say with high confidence that the number of anonymous-source stories published by the Times in 2015 approached 6,000, out of roughly 88,000 individual articles, blog posts and columns from both the paper and wire services. (To view the full set of Times-authoredanonymous-source stories for 2015, plus news desk and front-page analysis as well as a breakdown of bylines, go to this public Google Doc.) But I’m convinced the exact number is unknown by any mere mortal (or editor on Eighth Avenue).

That’s not to say that much of the Times’ anonymity output couldn’t be quantified. But to try to conduct a comprehensive census across 12 months of its editorial output is to realize the insidious nature of anonymous sources and the limitations they impose. So, like an astronomer trying to detect unseen forces in a distant galaxy, identifying unnamed sources similarly required looking for secondary effects in nearby objects.

Fortunately, theTimes’ confidential source guide establishes a clear policy for just such a thing. Whenever Times reporters cite an anonymous source, they are supposed to clearly spell out in an adjacent explanation that source’s relevant background and motivations for remaining anonymous. (Note my emphasis on “supposed,” which I’ll address later.) The accompanying phrasing that the Times and other news organizations have adopted for this—“upon condition of anonymity” or “insisted upon/requested anonymity”—thus became a guiding light for my anonymous source research.

Orbits of transparency and accountability

The myriad ways that anonymity creeps into the Times are not nearly that simple, though. Perhaps the best way to assess a year’s worth of anonymous sources is to think of them as occupying three distinct orbits of accountability and transparency.

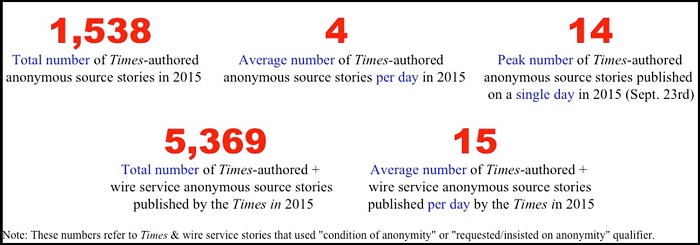

The closest, most visible of these involves anonymous-source articles that meet two criteria. First, they are authored by Times staff and, second, they follow the paper’s guidelines by “declaring” anonymity in the text. In 2015, the paper published 1,538 of these articles in print or online—an average of four a day—according to data pulled from the paper’s own Article Search application programming interface (API). (For more on the methodology of my data sourcing and analysis, see Tab J.)

Over the year, this anonymity followed a steady daily rhythm, but it did have ebbs and flows. On 12 different days in 2015, for example, no new anonymous-source stories were authored by the Times. Conversely, on September 23, the paper produced 14 anonymous-source stories in a single day.

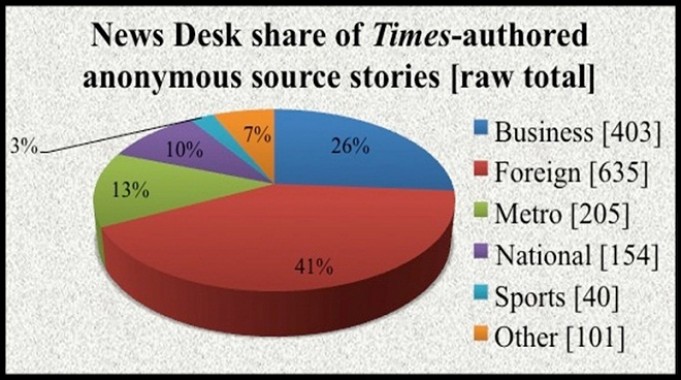

Not surprisingly, four major news desks—Foreign, Business, Metro and National—accounted for 9 out of 10 anonymous-source articles in the paper. The Foreign desk’s share of anonymous-source stories topped the list at 41 percent, followed by Business (26 percent), Metro (13 percent) and National (10 percent).

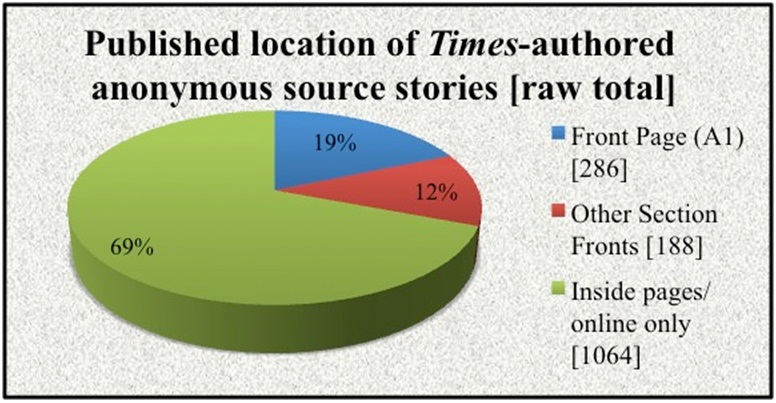

Far from being relegated to the back pages, a disproportionate share of these stories enjoyed prominent play in the print newspaper (which routinely correlates to priority placement on the Times home page as well). Nearly one in five—19 percent—of these anonymous-source stories ran on the front page (A1) last year. Another 12 percent were published on a section front, like Business Day.

Figures for 2015

Here again, the Foreign desk dominated: Its 163 articles represented more than half of all anonymous-source stories published on A1 in 2015. National (21 percent), Metro (11 percent), and Business (10 percent) desks accounted for virtually all the rest. In all, 286 anonymous-source stories ran on A1 of the Times in 2015, or roughly one story on four out of every five days.

In one respect, this high-profile status makes sense.

Blockbuster revelations of wrongdoing often necessitate using unnamed sources to get an important story out, and last year the Times had several remarkable examples of intrepid reporting worthy of the front page. Consider the fantastic Deal Book series on widespread arbitration abuse, which heard from an unnamed “cruise ship employee” who was cruelly prohibited from suing her employer after she was drugged and raped by fellow crew members. Without the key details provided by numerous anonymous sources inside the U.S. military, this chilling account of the limited oversight given to Seal Team Six’s secret kill missions would not have been possible. Likewise, this sweeping exposé of the nail salon industry, though controversial, drew much of its narrative strength from confidentially giving voice to many voiceless immigrant women being preyed upon by ruthless salon owners.

Many, many more of 2015’s anonymous-source front-page stories were not like the above, however. For every confidential whistleblower quoted, there were dozens more unnamed “American officials” to be found; time and again, the powerful enjoyed the privilege of anonymity orders of magnitude more often than the powerless. All too often, the Times front page resembled a journalistic dumping ground for anonymous source-driven ego scoops, trial balloons, buck-passing and what University of London professor and media critic Aeron Davis calls “inter-elite communication.”

Moving beyond this first orbit, there was an even larger ring in the anonymous-source solar system, which consisted of stories reported and written by wire services but published by the Times. (A majority of these were breaking news stories posted only on the Times website.) Last year, the combined total of these Associated Press, Reuters and other wire service stories came to more than 3,800. Combined with the total of Times-authored articles, the full-year figure of anonymity rises to more than 5,300 print or online articles—or nearly 15 anonymous-source stories every day.

Though these stories aren’t written by Times staff, the paper still exercises judgment over whether or not to run them and, thus, owns some culpability over their pervasive presence. Still, I deemed it unfair to hold the paper responsible for any systemic sourcing problems therein, since the Times cannot exert editorial control of how AP articles are reported and edited. As such, I omitted these wire stories from my deeper source analysis below.

This leaves the last, least visible orbit of anonymity, one that is populated by every hit-and-run citation by a Times reporter of a “senior administration official” or “Western diplomat” or “person in law enforcement” that offers nothing else by way of context to the reader. Nearly invisible yet stubbornly common, these deeply embedded anonymous sources act like the journalistic equivalent of dark matter. Remember how Times policy says all anonymous sources are supposed to be coupled with an explanation and reason for granting it? Well, every one of these examples fails to live up to that promise. Of all the ethical shortcomings of the Times’ anonymity practices, the continued existence of drive-by anonymity ranks among the worst.

Accounting for all these “dark matter” anonymous sources through the paper’s API proved to be impossible. Instead, in a manual search of a few hundred stories, I turned up several dozen anecdotal examples. While these results are by no means a statistical sample, nevertheless I’d still conservatively estimate that hundreds more of these latent anonymous sources were cited by the Times in 2015. That number could be even higher, but again, neither I nor anyone at the Times knows the actual figure.

This granting of de facto anonymity can have a corrosive effect over time. As Saint Louis University professor Matt Carlson notes in his 2011 book On the Condition of Anonymity: Unnamed Sources and the Battle for Journalism, this practice can foster a culture of source entitlement, where on-the-record attributions become exceptions rather than the rule. Once this culture becomes entrenched, it becomes that much more difficult to hold those in power accountable and accurately inform the public.

“The reproduction of official voices, particularly without attribution, may be objective, but it is often not desirable,” Carlson writes. “The concept of autonomy lies at the heart of journalism’s arguments for its authority, but it elides the complicated ways in which journalism is woven into the very culture it strives to cover from a distance.”

This New York Times story (7/23/15) about Hillary Clinton’s emails required two corrections to retract claims made by “senior government officials.”

The risks from blurring those lines became painfully clear in two of the Times’ biggest corrections last year, both of which involved the use of ‘dark matter’ anonymous sources. Two major front-page stories—about a supposed “criminal inquiry” into Hillary Clinton’s emails and on the San Bernardino terrorists’ online presence—both had to be walked back (sometimes more than once) after key claims initially provided by, respectively, unspecified “law enforcement officials” and “senior government officials” turned out to be wrong. Also worth noting: Both corrected articles violated the Times‘ confidential source policy—both before and after the correction ran. A close reading of how each story failed suggests the act of adding the missing context for the anonymous sources might have forewarned the reporters—two of whom shared a byline on both flawed stories—of potential problems before publishing.

Anonymity at the granular level

That two veteran investigative reporters—here, Matt Apuzzo and Michael S. Schmidt—were involved in multiple anonymous-source stories going sideways within the span of five months is striking…but also, in a way, unsurprising. For certain high-profile beats and subjects—like national security, foreign policy and national politics—relying on anonymous sources has long been both an occupational necessity and hazard.

In fact, a 1993 Journalism Quarterly study of major newspapers by Daniel Hallin, Robert Karl Manoff and Judy Weddle found that 48 percent of executive-branch sources and 32 percent of congressional sources went unnamed in national security articles. More than two decades later, little has changed. In a public editor’s column from 2013, Times national security editor Bill Hamilton (10/13/13) complained: “It’s almost impossible to get people who know anything to talk…. So we’re caught in this dilemma.”

Read the rest at http://fair.org/home/journalisms-dark-matter/

Reed Richardson is a media critic and writer whose work has appeared in The Nation, AlterNet, Harvard University’s Nieman Reports and the textbook Media Ethics (Current Controversies). You can follow him on Twitter at: @reedfrich.