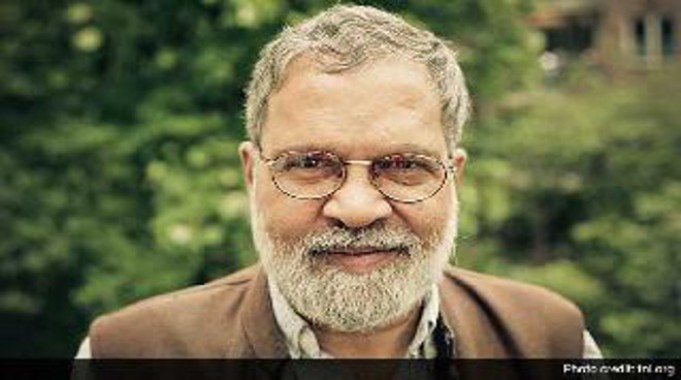

Praful Bidwai: tribute to a scholar journalist

In the age of Wikipedia, Praful was the person you called for things you could not find on the Net, or discover after a Google search.

AMIT SENGUPTA recalls a scholar, academic, teacher, friend, comrade and connoisseur. Pix: Praful Bidwai, NDTV.com

Praful Bidwai’s untimely death signifies the end of the era of the scholar-journalist. He belonged to that rare tribe of editors for whom newspapers were not just a business or a brand but a means to inform, persuade and change, and to contribute to the existing knowledge on everything – from politics and society, political-economy, science and technology, environment, strategic affairs, and, specifically in Praful’s case, climate change, the anti-nuclear and anti-militarisation campaign, and people’s movements across the most invisible and remote terrains of India and elsewhere.

He was certain in recent times that the new Land Acquisition Bill has the potential to unleash mass grassroot forces of turbulence against both crony capitalism and the communal and Right wing forces now enjoying a brute majority in Parliament. From Kudankulam and Jaitapur to Niyamgiri and Kalinganagar, from the remarkable turn of events in terms of the rise of progressive, Left and democratic forces in Greece or Spain, to the paradigm shift from the revolution of the bullet to the revolution of the ballet in Latin America, his heart would beat relentlessly on the Left side of history.

And yet, neither his heart nor his mind was an open-and-shut case. He belonged to a tribe that we see less and less of. Despite his Left leanings, he would not compromise on the authenticity of evidence, facts, objectivity and truth. A compulsive non-comformist, he would abhor dogmatism and sectarianism, and celebrate contradictions and differences. For him, indeed, all the windows of enlightenment were forever open, a kaleidoscope of factuality and truth beckoned him always, he would test the boundaries of his knowledge, and certainly not allow himself to fall into the comfort zone of half-baked knowledge systems or the compromises of mediocrity.

That is precisely why his articles, essays, lectures and books were not underlined with prejudice and clichés. Instead, they would be clear, on-the-dot, on-the-spot, exploring the bitter realism of our everyday life with a rigour, lucidity and transparency, absent in most forms of contemporary Indian journalism. That is why readers across the Right, Centrist and Left spectrum respected his writings, with or without a critical footnote.

His genuine curiosity, his encyclopaedic knowledge, his empirical and scientific objectivity, his academic rigour and research, and his high rate of journalistic productivity, published across the world, remains a testimony to his genius and hard work.

Witness his edit page article in The Times of India on January 2, 2008, titled, ‘Why Gujarat is Special’. He wrote: “Although ‘Hindutva laboratory’ Gujarat has been under full or partial BJP rules since 1990, its communalism goes back a long way. Modern India’s first recorded communal riot occurred in Gujarat in 1713. No less important was the Hindu-Muslim violence of 1893 at Somnath, whose effects were felt nationally and debated in London, leading to the famous Hunter inquiry. The politics of revenge for perceived past injustices struck deep roots in Gujarat under the influence of Dayanand Saraswati’s Arya Samaj and the ‘shuddhi’ (reconversion from Islam) movement active in the 1920s led by Swami Shradhanand…”

One of his last syndicated columns on the BJP regime’s one year was perhaps the finest amidst a media deluge of much ‘bending and crawling’. Surely, Praful was not only a symbol of a high moral compass and fearless journalism, in a certain sense, he was also a conscience-keeper of the media, howsoever the mainline print media tried to ignore him.

He wrote: “When Narendra Modi arrived in New Delhi to be sworn in as India’s prime minister, he flew in a private aircraft belonging to the Adani group, although he could have taken a commercial flight or a chartered plane. On landing, he was greeted with a communal-military slogan, Har Har Modi. The two events showed where Prime Minister Modi’s loyalties and priorities would lie: with Big Business and Hindutva, both of which he had served with pious zeal in Gujarat since the anti-Muslim pogrom of 2002 and through crony-capitalist deals later.”

Praful was relentless. He would move from one terrain of research to another with an unimaginable speed, his high productivity and measured arguments substantiated with academic rigour and journalistic fact-checking. He would pester reporters on the beat, chase his sources, take briefings, update his data before each article. This was no didactic propaganda. He authored South Asia on a Short Fuse and co-authored with Achin Vanaik Nuclear Politics and the Future of Global Disarmament. His last book was The Politics of Climate Change and the Global Crisis: Mortgaging Our Future. His book on the challenges before the Indian Left was almost ready for publication. He was thinking of positing the metaphor of ‘Phoenix’ as the title of the book, signifying the resurrection of the Left. His huge spectrum of writings, across diverse subjects, were a sum of great brilliance and much hard work. Not many journalists these days can lay claim to such a legacy.

And yet, he loved his occasional forays into Jama Masjid in old Delhi, especially during Ramzan, and he loved the ‘bheja curry’ insisting on fresh tandoori rotis and freshly cut onion. Often little details and zigzags would mark his non-conformist mind; like a whiskey with water at room temperature, and with roasted ‘paapad’, his love for east Bengal style fish, Marathi and Gujarati veggie food, or his abhorrence for a ‘business card’ on the mobile, or his not-so-hidden distaste for those who were obscenely loud. From the Press Club of Bombay to its midnight streets, to the Press Club of India and the old paan shops, he knew every zigzag and bylane.

In the age of Wikipedia, Praful Bidwai was the person you called for things you could not find on the Net, or discover after a Google search. From the earliest stories of the working class movement in Bombay, to little details about countries, cuisines, cultures, he would know impossible things, sensibilities, experiences.

He introduced us to the genius of Ulhas Kashalkar, one of the finest Hindustani classical vocalists today, on a misty December night at the Kamani Auditorium in Delhi. We were still so engrossed with the music, much after the show, that we forgot our way to the Press Club before the bar shut at 10.30 pm. He narrated to us intimate details about greats like Bhimsen Joshi and Kumar Gandharva, Habib Tanvir and MS Sathyu, among others, and insisted that we listen ‘live’ to Kalapini Komkali, Kumar Gandharva’s daughter. But he was not rigid. He knew I loved old Hindi film and IPTA songs, so there we were singing Sahir, Kaifi, SD, Rafi, Talat, and, of course, Salil Chaudhury, often in chorus.

So it was Kumar Gandharva playing softly on Saturday morning, June 27, at the Lodhi electric crematorium, where Praful’s body was brought from Amsterdam where he died. Amidst tears and flowers, songs and slogans of Lal Salaam, there was also a Palestinian flag sent by the Palestinian embassy as homage to a man who always stood for the Palestinian cause.

His body draped in the flag of the Coalition for Nuclear Disarmament and Peace (CNDP), for which he dedicated much of his life and writings, Praful Bidwai, great old fashioned journalist, scholar, academic, teacher, friend, comrade and connoisseur, departed on his last journey.

Goodbye Praful. Surely, as the song goes, this was, not the way, to say, goodbye.

Subscribe To The Newsletter