Maharashtra’s new law: high only on political symbolism

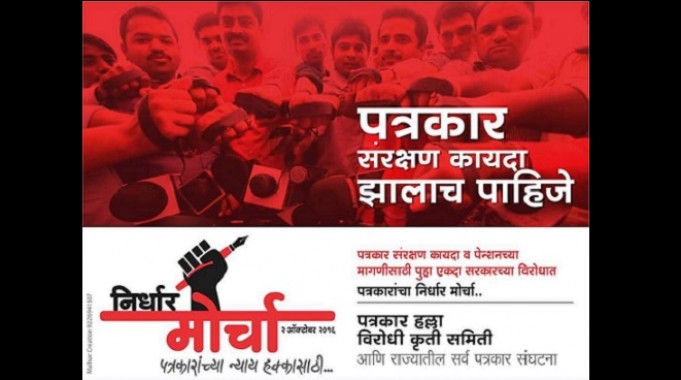

As reported last month on The Hoot, the State of Maharashtra has enacted a new law called the ‘Maharashtra Media Persons and Media Institutions (Prevention of violence and damage or loss to Property) Act, 2017'. The legislation was reportedly enacted in response to the demands by mostly rural journalists in Maharashtra who have been seeking legal protection against attacks.

Put briefly the law makes it a cognisable and non-bailable offence to indulge in violence against a media person or the premises of a media institution. All such cases are required to be investigated by a Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) and carries a prison term of 3 years along with a fine of Rs. 50,000. In addition the media person or media institution can recover compensation for any medical expenses or physical damage to their movable or immovable property.

Whom does the new law cover?

The definition of “media person” is quite broad. The main part of the definition reads “media person means a person whose principal avocation is that of a journalist and who is employed as a journalist, either on a regular or contract basis, in, or in relation to, one or more media institutions”. The definition then illustrates the kinds of people who are included in the definition. This list does not mention ‘stringers’ and one line of argument taken earlier on the Hoot is that the law excludes stringers. I would argue otherwise.

The operative term in the definition of “media person” is a “person whose principal avocation is that of a journalist” and who is employed either on a regular or contract basis. It can be argued that the principal avocation of “stringers” is journalism and that they are in effect employed on a contract basis by newspapers because they get paid for each of their stories. That they aren’t mentioned in the illustrative list in the definition is of no concern because the definition is “inclusive” and not exhaustive. Even persons not mentioned in the illustrative list can still be included as long as their “principal avocation is that of a journalist” and as long as they are not specifically excluded by this definition.

Does this law cover any new ground?

The definition of ‘violence’ in the legislation reads as follows: “means an act, which causes or may cause any harm, injury or endangering the life of any Media Person during the discharge of his duty as a Media Person, or causing damage or loss to the property belonging to any Media Person or Media Institution.” This vaguely worded definition basically covers a series of offences against the human body and property that are anyway criminalised under Chapter XVI of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). Most violent crime is cognisable and non-bailable making it possible for a police officer to arrest such persons without a warrant. The court may then grant bail at its discretion pending trial. Similarly the Code of Criminal Procedure (Cr.P.C.) does make it possible to compensate the victim of a crime. Therefore this new law offers no more protection than already offered under the existing law.

As mentioned in an earlier column in The Hoot, there is the possibility that the new law may actually dilute protection because unlike the IPC where punishment for causing “grievous hurt” is ten years in prison and for “attempt to murder” it is life in prison, the new law penalises violence against journalists with only three years in prison. Thus if the police decides to charge the accused only under the new law and not under the IPC it will in effect reduce the punishment for the accused. However it should be noted that the general practice of criminal prosecution in India is to charge an accused under multiple penal provisions in the hope that at least some charges will stick.

How is this new law going to help protect journalists?

The safety of any particular person or class of persons is contingent not just on the text of the law but also the competence of the state to enforce the law. Too often in India, the police is reluctant to enforce the law due to acts of commission or omission by the political leadership. A new law creating new classes of offences isn’t going to guarantee that the police act with more alacrity when faced with reports of violence against journalists.

The reporting on the new law

The new law has been welcomed by most journalists. The Mumbai Press Club released a statement praising the Chief Minister of Maharashtra, saying: “We thank Fadnavis for providing us with a legal deterrent which will be effective in ensuring safe working conditions for the working journalists…..Henceforth, we will expect the law enforcement agencies to apply the law whenever needed to bring the accused to book."

Similarly the International Federation of Journalists and the National Union of Journalists of India, hailed the law as a ‘landmark’. The statements released by both organisations is reproduced below:

NUJI President Ras Bihari said: “The sincere efforts of the NUJI and its district units to build a pressure on all state governments in the country have paid off. The NUJI will take the Maharashtra law as a model and lobby with other states to pass similar legislation.”

The IFJ said: “The IFJ welcomes the passing of the legislation to protect journalists in Maharashtra state and congratulates its affiliates and journalists unions for the achievement. Such laws will help greatly to address violence against journalists and reduce impunity for attackers. Such security can help ensure that journalists work independently. The IFJ demands the effective implementation of the law; and urges other state government and the federal government of India to consider such legislation.”

Both statements are grossly exaggerating the impact of the new law. This law is unlikely to change anything on the ground for reasons already discussed above. That said, it would be unfair to ignore the political symbolism of this move by the Maharashtra Legislature. At a time when high ranking politicians of the BJP have called journalists “presstitutes” and other such degrading epithets, journalists can take some comfort in the fact that a BJP ruled legislature is waxing eloquent about the importance of protecting journalists. It sends an important signal to the community about journalists that here is a Chief Minister and legislature that cares about journalists enough to enact a law. It also sends out a signal to the police and prosecutors that the protection of journalists is high on the political agenda. The political symbolism of this new law is thus more valuable than the words contained in the law itself.