The giant who straddled Nehru and Bhagat Singh

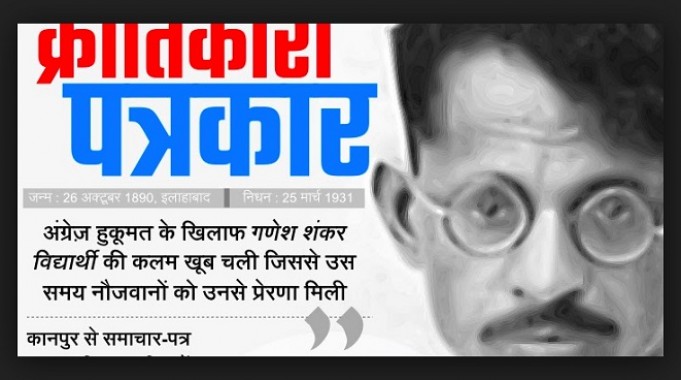

While several journalists and newspapers made an important contribution to the freedom movement, the contribution made by Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi and his newspaper Pratap is unique for many reasons.

Firstly this was a rare newspaper in that, during the critical decade of 1920-31, it was as well known for its support of the Gandhi-led Congress movement as it was for its sympathetic coverage of the revolutionary movement led by Shahid Bhagat Singh and Chandra Shekhar Azad.

Gandhiji and Jawaharlal Nehru had the highest praise for Vidyarthi while Bhagat Singh and his colleagues consulted him on important issues. Bhagat Singh also worked for Pratap for some time as an assistant editor of sorts and contributed articles under the pen name of Balwant Singh. As a meeting point of these two waves of the freedom movement, at a very sensitive period, Vidyarthi and Pratap played a unique role unsurpassed by any other editor or newspaper of those days.

Secondly, both as a freedom fighter and a leading editor, Vidyarthi always emphasized the importance of communal harmony. Ultimately, he sacrificed his life at the young age of 41 for Hindu-Muslim unity while trying to rescue victims of communal violence in 1931.

Thirdly, Vidyarthi and his paper combined their support of the freedom movement with constant coverage of the struggles of peasants and workers. Pratap published several detailed reports of the oppression of peasants by zamindars. To mention only a few, it carried reports on peasants on indigo plantations, firing on the agitating peasants of Rai Bareilly, and the many-sided oppression in Champaran. Other memorable reports published in Pratap included reports on the struggles of textile workers and on various forms of slave labour.

Reports which are likely to fetch journalism awards these days invariably fetched prison sentences in those days. Not surprisingly, Vidyarthi had one foot in prison while bringing out Pratap. In fact, his time at the helm of the paper, guiding and editing Pratap, was disrupted by as many as five prison sentences.

In addition, there were other threats all the time, including raids on the offices and press as well as many defamation cases filed by powerful and extremely rich persons and institutions. Perhaps the greatest difficulties were created by the cases that were filed in the fiefs of various royals and their riyasats as even the pretence of a justice system did not exist. Undeterred, Vidyarthi went ahead with publishing daring exposes of the oppression faced by people under the rule of royal families such as those of Bijaulia, Gwalior and Bharatpur.

The prison sentences which Vidyarthi endured served to strengthen his role as a civil liberties activist and writer. He himself wrote about the terrible conditions inside prisons faced by freedom fighters and the need for urgent jail reforms. As to his own experiences, this astonishing editor used his time in jail to translate several of Victor Hugo’s work into Hindi.

Inspiring Life

Starting his life as a journalist in Kanpur with journals like Saraswati and Abhyudya, Vidyarthi soon attracted attention due to his hard work and deep commitment to public causes. When, at the very young age of 23, he decided to start a weekly magazine called Pratap devoted to his social concerns, several friends and supporters such as Shiv Narain Mishra and Narayan Prasad Arora came forward to help him.

Despite the many problems faced by the new magazine and the disruptions created by the government and other forces, people needed a courageous magazine and responded so well that in the middle of all the problems, a big decision was taken in 1920 to convert it into a daily newspaper.

Subsequently this Kanpur-based newspaper became widely known as the one widely read media outlet where stories relating to the misdeeds of the colonial government, as well the royals in collusion with the regime, were most likely to be published and that too in the most fearless way.

By 1930 Pratap became the most widely circulated newspaper in the United Provinces. One of its great strengths was its ability to create an effective network of reliable local stringers instead of relying on the same English news agencies as other publications.

Although Vidyarthi had to quit as editor for short periods because of jail sentences and legal complications arising from defamation and other cases, he came back repeatedly to edit and guide the newspaper. Even during the period when his name may not have appeared as the editor in a formal way owing to the fact that he was in prison, he was widely regarded as the newspaper’s single most important asset.

The growing popularity of the newspaper and its editor made it increasingly difficult for the colonial government to initiate frequent action against them without attracting criticism. In 1925-26 Vidyarthi was elected to the UP Legislative Council. In 1929 he was elected to head the Congress in this important province.

The British government was most troubled by this development since Vidyarthi enjoyed the confidence and support of the Congress as well as the revolutionaries. He was arrested in May 1930 at a time when the popularity of Bhagat Singh and his companions had begun to peak. He came out of prison on March 9, 1931 and immediately plunged deep into important work.

When Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were hanged by the colonial government on March 23, protests broke out in various parts of the country and Kanpur, under Vidyarthi’s leadership, was all set to emerge as a leading centre of such protests. At this stage, to prevent this happening, communal riots were deliberately instigated and Vidyarthi was killed during these riots while he was on his way to the most dangerous spots to rescue trapped people.

Gandhi paid his tribute to Vidyarthi with the words: “His blood will become the cementing bond for inter-faith harmony.” Jawaharlal Nehru said: “In his death he has taught a lesson that we in our life can’t equal for years.”

After Vidyarthi's death the role played by Pratap declined gradually though it continued for some years thereafter.

Bharat Dogra is a freelance journalist who has been involved with several social initiatives and movements. He is also the co-author of a booklet on Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi with Reshma Bharti.

Sources

1. Salil, Suresh, (Editor): Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi Granthavali (collected works), Anamika Publishers and Distributors.

2. M.L. Bhargava: Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi Publications Division, Government of India.

3. Francesca Orsini: The Hindi Public Sphere 1920-1940, Language and Literature in the Age of Nationalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

4. Gyanendra Pandey: Mobilisation in a Mass Movement: Congress ‘Propaganda’ in the United Provinces 1930-1934, Modern Asian Studies, 9 (2) 1975.

5. Kama Maclean: A Revolutionary History of Interwar India, Penguin Books.

6. Reshma Bharti and Bharat Dogra: Jeevan-Mrityu Dono Mein Prerna Srot Bane Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi, Social Change Papers, Delhi